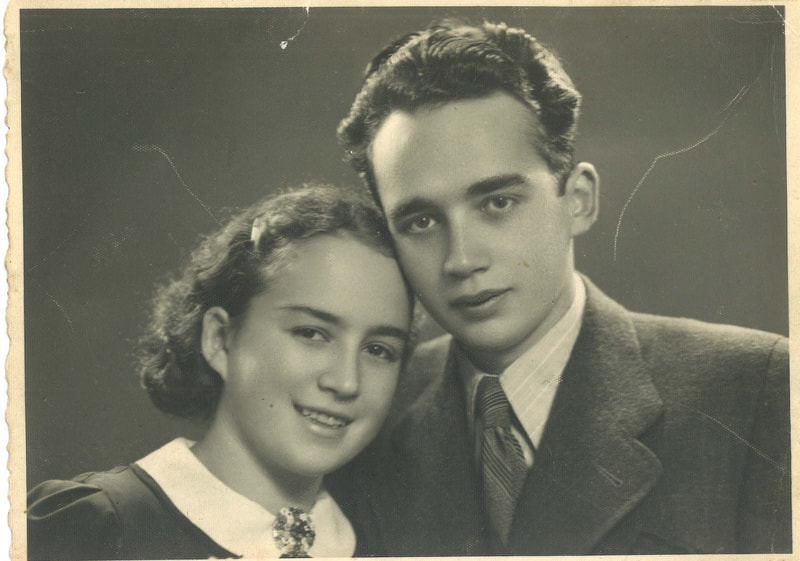

Chapter 5: Shades of Chanel No. 5By Rita Benn, daughter of Alice and Phillipe Benn

Growing up, I relished watching my mother get dressed. With her hair flattened, she reminded me of Marlene Dietrich, sultry and refugee-like. When she was ready to go out, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Barbara Walters seemed the more à propos mix. Fashion was my mother’s love, and elegance her trademark. Accompanied by the lingering smell of Chanel No. 5, it didn’t matter if my mother was going out to buy groceries or play bridge with friends. She was determined to leave the house as if she came out of a 1960s photo shoot for Vogue. It took forty years in Canada and chemotherapy appointments before she dared to buy herself a pair of sweats and sneakers. As a young girl, I regularly accompanied her to Bubnick’s, her Romanian dressmaker, where she was outfitted with Yves St. Laurent and Christian Dior lookalike designs. In the basement of Bubnick’s home, the two of them chatted in their Eastern European version of English about Jackie Kennedy’s latest hat or dress featured in Women’s Wear Daily. When I asked my mother why Bubnick’s speech sounded so heavily accented, she replied, “Is his accent more noticeable than mine?” I nodded. Puffing her chest proudly she told me, “I have an ear for languages: French, German, Yiddish, Lithuanian, Russian. English is the hardest of languages to learn. The earlier you start to learn a language the better. You’ll be happy later in life to be able to communicate with so many people.” Unfortunately, she was greatly disappointed by my poor intonation and lack of motivation to master any languages other than English and French. You could never tell by looking at my mother that she had suffered in any way. Her thin strands of blond hair were well coiffed into a bouffant elevated by her neatly tucked-in hairpiece. Nightly applications of Estée Lauder protected her face from showing the lines of wear and tear that marked each loss in her life. Though she was impeccable to the outside world, the pain of the Holocaust did not stop gnawing at my mother’s insides. I saw her tears streaming on Yom Kippur when she permitted herself to mourn all the relatives taken from her. With her new life in Montreal and her insistent focus on a pristine appearance, my mother tried to wipe clean the history that included her wartime years. The nine months of concentration camp incarceration, the itching from lice, the standing for hours on end in the rain while other inmates, family members, and friends collapsed or were shot. Even the first day of spring after our freezing Montreal winters could never fully bring her joy, as March 21st marked the anniversary of her mother Rebekka’s death. It didn’t matter how many times my mother spritzed her sweet French perfume over her clothes. She could not cover the stench of the Holocaust from seeping out. Despite her remarkable resilience, invisible ghosts of sadness hovered, casting shadows on the makeshift beauty of a life she tried to create for herself and our family. ADDITIONAL FAMILY RESOURCES [by Rita’s aunt] Ginate-Rubinson, Sara. Resistance and Survival: The Jewish Community in Kaunas, 1941-1944. Toronto: Mosaic Press, 2005; Second edition, 2011. |