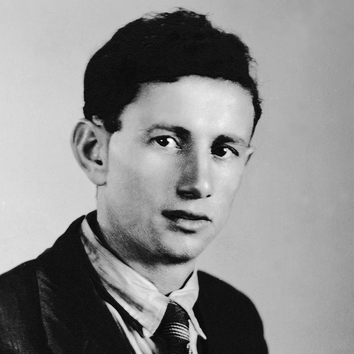

Chapter 9: Cutting CornersBy Phil Barr, son of Harold (Chaim) Rayberg

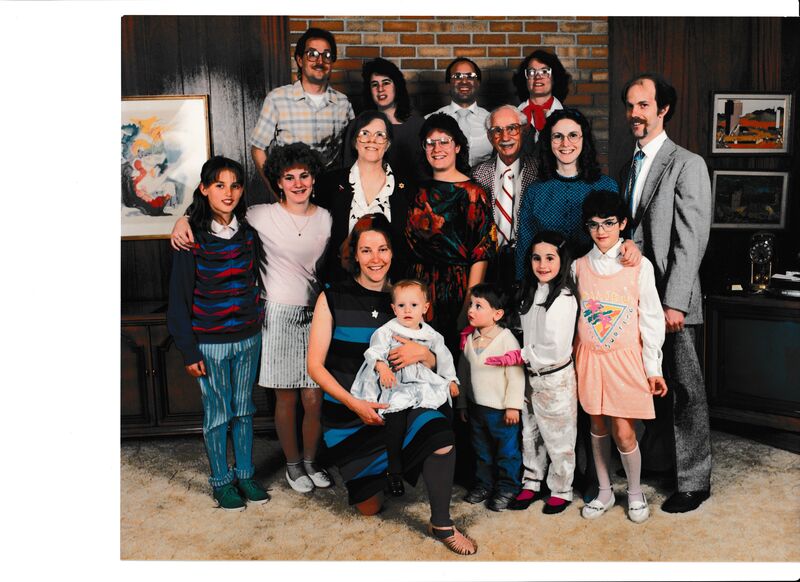

He passed away in a bed in Haifa, filled with tubes and wires. My oldest sister Lana, with whom he’d been living, described him breaking down in tears a few weeks earlier, wondering aloud, “How could I have left my mother?” When my father was seventeen, his mother told him, “Run.” Was that the first time he had cried since 1941? Possibly. I know I’d never seen him cry. Growing up, I remember Dad coming home after dark, long after Mom and us six kids finished eating. After shedding his work clothes and boxes of papers in the front hall, he heads for the kitchen. When I come in and give him a kiss, he’s leaning forward in his chair, hungrily slurping hot soup and laying slabs of butter on pumpernickel, his wool cap still on his head. He is already anxious to collapse into bed. In a ritual we have at the time, I ask for his change purse and go through it, looking for silver. If I’m lucky there might be a Mercury dime. By the time I’m eleven, dimes and quarters have already been clad for a few years, and silver coins are rare. I check the date and mint mark for my collection and toss the rest of the coins into the green sewing bag to put into paper rolls later. After eating, he might kiss several of us good night on his way to bed, but there are few words. Perhaps he’ll yell “Shahrrap-You” to silence an argument between us. The ongoing argument with Mom over money for household expenses would wait till morning. Fifty years later, that green box with the rolls of coins is still on the bottom shelf of my office. My father, by contrast, had nothing left from his childhood home. Despite my mother’s efforts to stop him, he worked seven days a week. Going to the junkyard was both habit and an escape. Since he saw everyone there as a ganif, especially the workers, he may have gone to prevent theft as much as to work. Trust in strangers, or in his family, did not come easily to Chaim. The double doors of the Rayberg house in suburban Oak Park, Michigan, were painted a deep orange, a loud sixties color. Fairly disheveled inside and out, we were that house on the block with a truck and three old cars in the driveway. Two more junkers waiting to be sold or fixed up parked in front. A bustle of kids and our friends, always coming and going. We grew up around the kitchen table. For dinner we had large bowls of fresh salad and a rotation of dishes meant to feed a hungry brood: spaghetti and meatballs, beans and franks, tuna noodle casserole, trays of Weight Watchers’ baked apples with red pop. We sang, argued, pushed, and grabbed. Insults and retorts were mostly delivered in good fun, but they were cutting, nonetheless. After dinner, food was left warming or on the table for Dad. His attitude about food was pretty basic: “A potato, boiled meat, and some fried onions. Now that’s a meal!” Thinking back now on those happy times, it’s hard to try to reconcile our “typical” suburban American upbringing with the history that brought my father to America, and to reflect on how that history inevitably influenced us. |